Wildlife

Introduction

In past, the forests of Bastar district have held large and varied wildlife population (Working Plan 1988). Like elsewhere the status of wildlife has been adversely affected here also. A drastic decline in the numbers of wild animals has taken place in the last 20 to 30 years (Working Plan 1988). This has been due to fragmentation of habitat, occupance of water sources by villagers, heavy use of forest resources, rampant fires and illegal hunting. Before the merger of state, shooting of wild animals was very common in Bastar district. After the merger of state in Madhya Pradesh in 1948, the shooting rules were reframed by the Govt. of Madhya Pradesh under the provisions of Indian Forest Act, 1927. Since the year 1972, shooting has been banned under the Wildlife Protection Act but hunting including the community hunt called ‘Parad’ by tribals is still prevalent, though illegal.

According to the information, available from the local people and forest department of Madhya Pradesh, wildlife was in abundance in the past in this area. Although the wildlife population is greatly reduced in the area, most of the species (tiger, leopard, hyena and jackal) are still found in varying numbers. Tiger which was once found in the study area in abundance has now become very scarce. Presence of the leopard in the area has been confirmed by the Forest Department Officials who had made compensatory payments for cattle lifting eight persons in the year 1988. Tribals also inform that the leopard usually frequents their habitat areas in search of food. Hyena, jackals and Indian fox are found in the forest and also near human habitations. Wild dogs are rare.

The Working Plan of Central Bastar Forest Division (1988) informs of abundance of nilgai, chinkara, chowsingha, samber, chital, barking deer and gaur in the area in the past. Among them chital, barking deer and gaur are still seen in the area. Sloth beer is found in the throughout the study area and is more common in hilly tracts. Swamp deer is extinct from the study area (Working Plan 1988).

The wild buffalo is a critically endangered species in India. From its earlier wide distribution in Central highlands there are none left in Orissa and Maharashtra (Divekar et al. 1979, Ranjit Singh 1982). They were commonly seen in the study area till recent past but have now disappeared from the area (Working Plan of Central Bastar Forest Division 1988). In Bastar, this species is now confined to small pockets in Indravati Tiger Reserve, Bhairamgarh Sanctuary and Pamed Sanctuary (Divekar and Bharat Bhushan 1988). Regarding avifaunal distribution, the area is rich and diverse, large numbers of migratory and resident birds still inhabiting the area (Working Plan 1988).

Present wildlife status

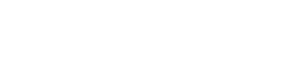

The richness of environmental attributes e.g. rainfall, soil, terrain and vegetational diversity are a strong pointer to high potential habitat quality. However, the eastern segment, being more flat in terrain, is largely cultivated. The western segments and the peripheral forest all around still have a good structure. Likewise the riverine islands have considerable potential habitat value for all wildlife, particularly birds and aquatic animals. The whole area, however, is subject to regular hunting by local people. The construction area is further disturbed by roads, movement and varied constructional activities. Despite some pockets in the lower submergence area, the construction area, the peripheral forest area both within and adjacent to the submergence still show evidence of wildlife presence. Fig – 6.1 shows the area surveyed for wildlife studies. Special attention was paid to locate additional study points near water sources e.g. river banks, pools and streams. For birds, a list of species recorded from the study area has been prepared.

Results of our fieldwork for the study of wildlife component are presented below:

Mammals

Queries with local people suggests that wild buffalo became extinct from this area relatively recently. Such local extinction is evident from the fact the fact that bulk of potential wild buffalo habitat in the flatter area along the bank of Indravati, stands largely diverted to cultivation and habitation. We found high density of domestic livestock signs all along the river in this area.

Signs of gaur were found at three locations in the forests all outside the submergence area but adjacent to the submergence area in Hitameta Reserve Forest and obviously these animals were also ranging in the nearby forests forming part of submergence area. Old hoof marks were found near a salt lick. All these sign of gaur were seen on hill slopes. The dependence of these animals upon the Indravati river or the lower reaches of tributaries nalas, where only water is available, is an inevitable conclusion.

A single sighting of chital was recorded and evidence of pellets seen all around. However, because of similarity between the pellets of goats and chital was not possible to estimate the abundance of chital. Still the villagers did confirm their presence. The degree of disturbance is however suggestive that their numbers cannot be significant.

One barking deer was seen. Dropping of barking deer were seen at two spots in the submergence area. Informants said that barking deer is common in hilly part of the area.

No tiger or its sign were present. One leopard was seen within the submergence area in the reserve forest of Narayanpur forest division. In addition, leopard scat and pugmarks were found at two places in the bed of Mander nala out side the submergence area. Jungle cat was sighted once in the construction area.

Hyena was sighted twice at two different locations in the construction area. In addition, its scat was also found once. Indian fox was seen twice on the road leading to the dam site from Barsoor village. Two jackals were seen together in the submergence area. Porcupine droppings were also seen on locations in the adjacent forest area.

Tribals of study area and other informants told us that sloth beer is commonly found throughout the area but we could not sight any animal. Droppings were, however seen at two different locations in the submergence area, one of them being very close to the dam site. Sloth beer is also reported to have attacked men in these areas, one case having been recorded in adjacent forest area.

Giant squirrel are common in the western segment of the submergence area. Although only one giant squirrel was sighted, a large number of nests were located at two distinct locations in the less disturbed portion of submergence area. Thirty nine nests were counted in a stretch of forest 1.5 km long and this suggests a fair abundance of giant squirrel. Most of the nests were located mainly on Sal trees. Tails of a freshly killed giant squirrel was also seen displayed in a hutment (Plate 6.1).

Troops of langurs were seen only on three occasions, but droppings were seen scattered throughout the peripheral forests. Rhesus monkey was reported to be present in the area but we could not sight any.

Pug marks of smooth Indian otter were seen on two different islands of river Indravati (Fig. 6.1). Their presence is further confirmed by the local fishermen. Otter scat was also collected from the bank of Indravati.

Reptiles

Turtles and snakes are a favourite food of local tribals and as a result have been under much exploitation. Common krait and common wolf snake were seen in the area. Skin of Indian python was seen displayed in a house.

The common garden lizard, forest calotes, common skink and snake skink were also seen on several occasions.

A couple of Gangetic soft shell turtles Utrionyx gangeticus) caught by local villagers in Indravati river were seen being sold in weekly market. Their flesh is relished. It is noteworthy that this turtle is quite rare and listed in Schedule 1 of the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972. Local people report the presence of mugger in Indravati river but we could not site any.

Fishes

Indravati and Bavardhrig rivers harbour a large number of species of fishes. Twelve species of fishes were confirmed from Indravati river flowing through the submergence area. All of them are being exploited for food and are also sold. List of species which have been confirmed from the study area is given in Table – 6.1 below.

Table 6.1: List of fishes sold in the weekly market at Barsur.

|

S.No |

Local Name |

Scientific Name |

|

1) |

BALIA |

Wallagu attu |

|

2) |

MARAL OR BHADIA |

Channa marulius |

|

3) |

BODH OR GOONCH |

Bagarus bagarius |

|

4) |

ROHU |

Labeo rohita |

|

5) |

CALBASU |

Labeo calbasu |

|

6) |

MIRGAL |

Cirrhinus mrigala |

|

7) |

CATLA |

Catla catla |

|

8) |

TENGRA |

Mystus aor |

|

9) |

SEENGHAD |

Mystus seenghala |

|

10) |

BHCHUA |

Clupisoma garua |

|

11) |

ALBOVADI |

Notopterus spp |

|

12) |

MANGUR |

Clarias batrachus |

Birds

Bird communities are a good index for monitoring environment because they are ecologically diverse (Jarvinen & Vaisanen, 1979) and use a wide variety of food and other resources. Most bird species have a relatively short generation time, consequently the may show quick responses to environmental changes (Steele, et. al., 1984).

In order to help fulfillment of study objectives our effort was addressed to finding out the diversity and abundance of bird species in the project area, more specifically in the proposed submergence area of the dam. Birds were recorded whenever they were seen during the study period. Locations of bird sightings were classified into different habitat type viz. forest, reverine and pond and ‘disturbed’ (e.g. habitation and agricultural area. The abundance of birds was recorded as rare, occasional ad common, based on the frequency of sightings.

A checklist of 127 species of birds representing 45 families was prepared (Appendix – 6.1) from these observations. They have been classified according to different habitat types and abundance categories. The distribution of bird species by habitat types and their overall abundance ratings are as follows:

| Habitat type | Number of species | Percentage of total |

| Forest | 56 | 44 |

| Riverine and small ponds (R) | 17 | 14 |

| Habitation and agricultural area (H) | 18 | 14 |

| Forest/ habitation and agricultural area (F/H) | 32 | 25 |

| Riverine/habitation and agricultural area (R/H) | 4 | 3 |

| Total: | 127 | 100 |

| Abundance rating | Number of species | Percentage of total |

| Rare (1-5 sightings) | 25 | 20 |

| Occasional (5-20 sightings) | 41 | 32 |

| Common (more than 20 sightings) | 61 | 48 |

| Total: | 127 | 100 |

Forest specie

Fifty six species were recorded in and at the edge of Protected and Reserved forest. They account for the highest proportion (44%) of all the species. Most of the forest species sighted were either rare (1-5 sightings in total study duration) or occasional (5-20 sightings in total study duration). These include wood-peckers, orioles, flycatchers and hornbills.

Riverine and small pond specie

Seventeen species (14%) were recorded in riverine and small ponds areas. Eight species were seen in riverine habitat. These include open bill stork, white stork, black ibis, and lesser whistling teal. Most of the species were rare. Black ibis and lesser whistling teal were recorded only once. Nine species were recorded from small ponds and other water logged areas. Pond heron, little egret, median egret, little ringed plover, common sand piper and spotted sand piper are some of the species from these areas. White breasted water hen, white breasted kingfisher and small blue kingfisher were seen in riverine habitat and near the ponds.

Forest/Habitation and agricultural area species

Four species were common in riverine forests and their edges with habitation areas. These are redwattled lapwing, yellowheaded wagtail, grey wagtail and pied wagtail.

Family Muscicapidae represented the highest number of species (17) while families Threskionithidae, Anatidae. Falconidae, Turnicidae, Rallidae, Rostratulidae, Laridae, Caprimulgidae, Coracidae, Upupidae, Hirundinidae, Sittidae, Dicaeidae and Zosteropidae represented only one species each.

Six species of woodpackers and four species of bulbuls were recorded which suggests the potential richness of woodland bird habitat. Three species each of kingfishers and parakeets were seen in the study area. Among the bird of prey, pariah kite and shikra were commonly seen while marsh harrier and Indian crested hawk-eagle were sighted only twice. The white backed vulture was also fairly common. The water birds were scarce because the study period fell during the March, April and May and by that time most of the migratory birds had gone. Even so the non-migratory water bird species were numerous including egrets, openbill stork. White stork, lesser whistling teal, painted snipe little ringed plover, common sandpiper and spotted sandpiper.

An interesting comparison emerges out between our list and that of Kanha Reserve Tiger M.P. (Newton et. al. 1986). In Kanha Tiger Reserve a total of 225 bird species have been reported in a survey for a period of over three years. From the study area we recorded 127 species of birds in a period of three months of the not so favourable season for survey. Whether the diversity of avifauna and the habitat supporting the avifauna is good needs to be evaluated with a more systematic study over a period of atleast one year to cover the different seasons.

Certain population differences characterize the different communities. Preference by a few vary common species is typical of disturbed habitats and greater equitability of species often typifies the more complex and less disturbed habitats (Patrick 1963, MacArthur 1972). Our study also indicates that a few common species like black drongo, Indian roller, mynas, doves and larks occupied the disturbed areas. In the forest or less disturbed habitats the number of species is more and most these species were occasional or rare.

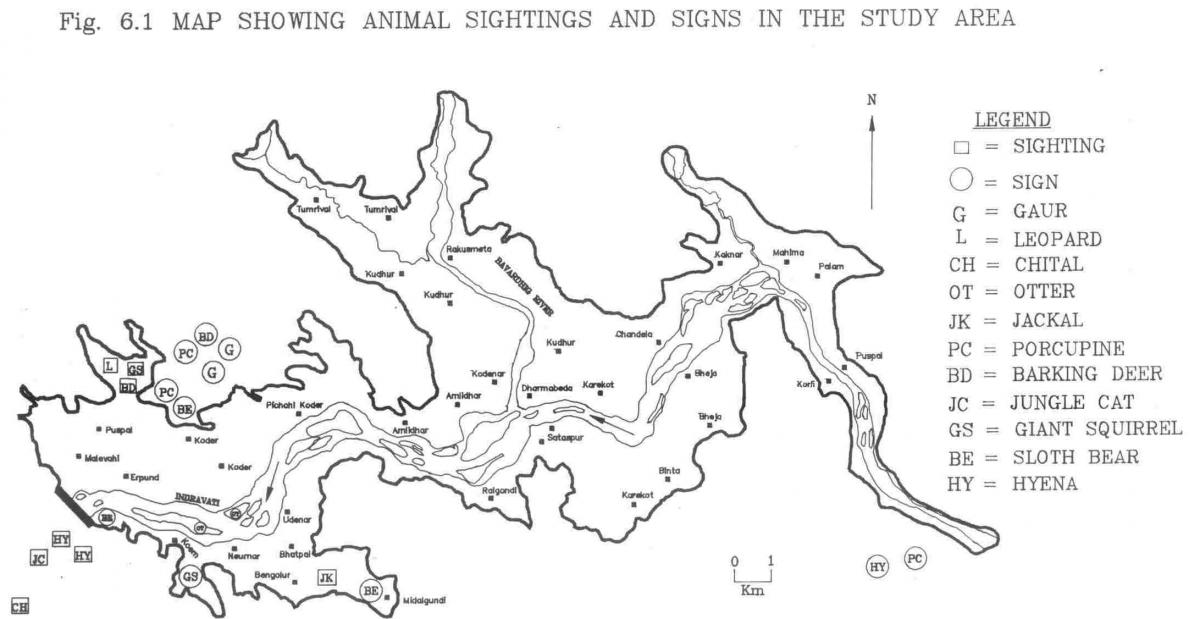

Human pressure on the forests and disturbance of river banks are existing constraints. Hunting is also fairly common and a few instances of bird hunting were recorded by the research team (Plate 6.2

Among 127 species recorded from study area, some have specific preference to certain trees or bushes for their requirements (nesting, feeding, roosting etc.). Because of the short study period, observations establishing association of birds with specific trees or bushes were not possible. During the study, attention was paid to locate the hill myna which is a locally endangered bird. Four sub-species of hill myna (Gracula religosa) are found in India. Easter hill myna (Gracula religosa peninsularis) has reported from Orissa, eastern Madhya Pradesh and northern Andhra Pradesh (Ali and Ripley 1897). In Madhya Pradesh, Bastar is its main habitat and it is also called Bastar myna (Ali and Ripley 1987). This bird has been reported from this area in Working Plan (1988) but no specific locality is mentioned. Until some years ago the bird was regularly sold in local weekly market for its popularity as a bird capable of mimicking human voice. Attempts to locate the bird in the study area proved futile.

Summing up, the submergence area has diverse forest and riparian habitats and has a rich potential for avifauna. However, the human pressures and disturbances stand in the way of realising their potential.

Likewise it can be concluded from our observations that overall wildlife status of the area id poor despite a high potential. As far as larger animals are concerned; they are present in small numbers. Fig. 6.1 shows that most of sightings and signs of larger mammals were recorded in the hilly area away from the river because the river vicinities are occupied and disturbed.

Potential for wildlife

The forest in and around the submergence area is diverse. Ninety eight species of trees and forty two species of shrubs were identified from the study area during our study. Forest land is classified into three categories : Reserved forest, Protected forest and Orange forest. Orange forest which is unclassified and present mostly in flatter area is highly disturbed because of the presence of human settlements and almost has no food and cover value for wildlife. Structure of Reserved forest and Protected forest is good and so is the regeneration status. The diversity of fodder and fruit bearing trees, shrubs and grasses is impressive. The cover conditions, except in the habitated and disturbed area are also good as established by our transect studies. Bamboo occurs extensively in the miscellaneous forest and provide good fodder and cover value. Indravati and Bavardhrig rivers are the permanent sources of water. Besides these, the lower reaches of some nalas retain perennial pools. Except summer, water for most of the year is available in seasonal nalas. Fragmentation of forest by villages, human settlements and cultivation patches has advanced but is limited only to the valley area.

The forests in the area occur in contiguous blocks. For example: the reserved forest of Naraynpar Forest Division (Compartment Nos. 225-341) and Protected forest of Central Forest Division (Compartment Nos. 51 to 132) form an undisturbed and unfragmented forest block. These forest have a high potential for varied wildlife. Evidences of gaur and barking deer were found in this unfragmented forest patch.

Unlike most of the forested area of India, Bastar relatively has a much lower population of cattle. During our survey, we found that mostly the valley area along the Indravati river is being used by the cattle. The forest on slopes is free from livestock grazing pressure and is devoid of weeds. Its fodder value for wildlife is enormous.

The riparian are is potentially rich and a major habitat supplement for all wildlife besides supporting its own typical species. Some of the islands of the Indravati river are quite large in area and are open. They can be considered as good potential habitats for large aquatic animals (otter, mugger etc.). The river itself, polluted, perennial and given to grassy beds where wide and deep poles at many places id ideal for fish, turtles and water dependent birds. Minor forest products like tendu leaf and mahua flower are collected by the tribals. Forest fires to clear the graound surface for mahua flower collection are common. The ash of the litter flows down to their fields as fertilizer. Wood cutting for their own use (poles and fore wood) is also common. Yet the adverse effects of these activities are apparent only in the forests have good density and vertical structure.

In conclusion it can be stated that the habitat diversity and condition is also fairly good notwithstanding the pressures of the local people. The potential habitat capacity is excellent, although because of annual fire and sustained hunting by villagers the present status of wildlife is rather poor.

Investigations downstream of Bodhghat for wild buffalo

Four small populations of wild buffalo survive in Bastar. The largest is in Indravati Tiger Reserve (Pandey 1980) quotes the park’s census figure as 127 for 1987.

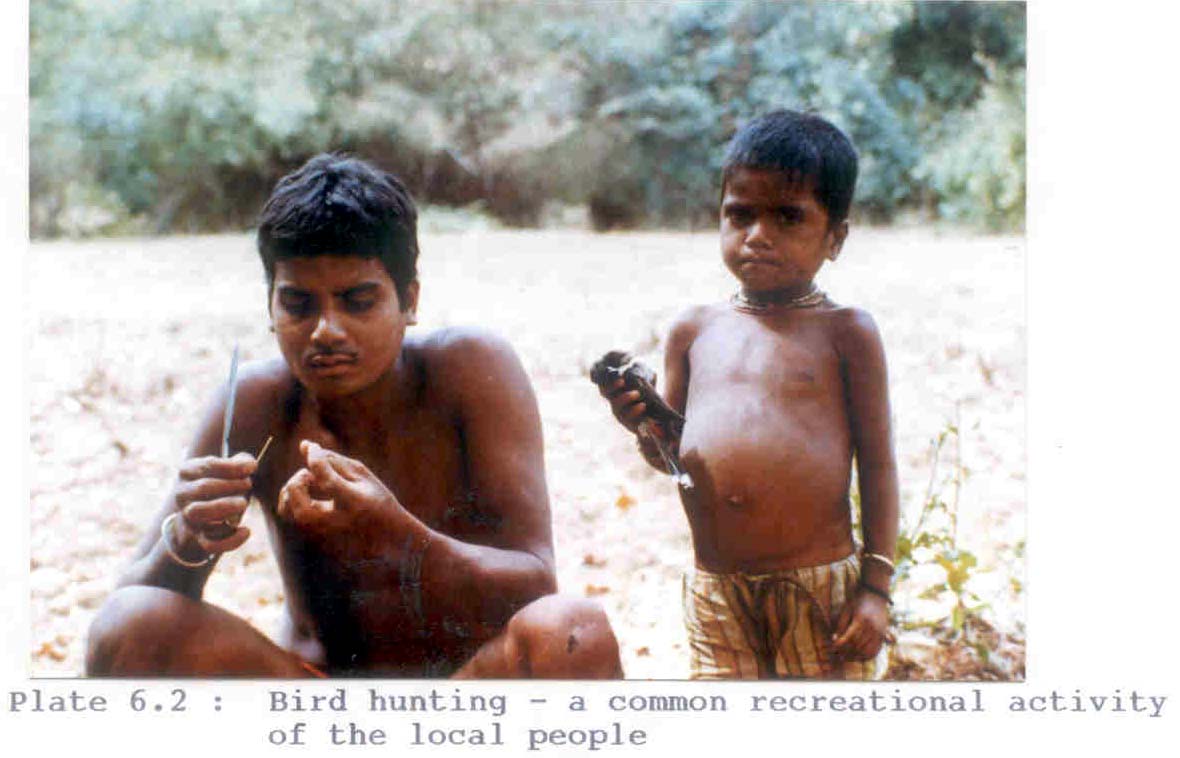

Divekar and Bhushan (1980) give an estimated figure of 70 – 80 animals in 1988. A second population is 60 km upstream in Bhairamgarh Wildlfie Sanctuary, with possibly 10 – 15 according to Divekar and Bhushan (1988) and may be 20 -25 according to Sanctuary authorities. Both the areas extend upto Indravati river.

A special survey of the areas downstream of Bodhghat projectwas conducted to monitor wild buffalo habitat and its use. In Bhairamgarh sanctuary we saw fresh evidence of wild buffalo herds atleast at two places. They had used teh river bed grasslands in compartment 84 and 85 (Fig. 6.2). Further, a little older hoof mark evidence was also recorded from compartments 83 and 87 in low lying grassy areas, somewhat removed form the river bank. Dhangajusa nala and its valley forests interspersed with low lying grasslands on the bank and in the bed of Inderavati river, constitute the main habitat of wild buffalo in Bhairamgarh sanctuary.

No data on the regime of water releases from the Bodhghat project was provided by the Project authorities. However, the water releases are going to depend upon the regime of power generation. As the project will essentially be catering to meet the peaking power loads, the diurnal regime is bound to have heavy fluctuations, with the discharges between 6 PM to 10 PM being really heavy.

Last Updated: December 12, 2015