Discussion

In a forested tract inhabited by forest dependent people the main environmental values likely to be impacted upon a development project which imposes drastic and substantial changes in the prevailing Landuse, can be divided into two classes viz.:

1. Natural values

Biodiversity and wildlife, covering both flora and fauna.

Ecological processes.

2. People related values

Socio-economic

Cultural

In Bastar the two types of values are intricately intertwined. They together form the basis of an integrated landscape that had held together since millennia but which, unfortunately, even without the Bohdhghat project now portends signs of disintegration. The traditional Landuse and resource utilization practices now seem to be undermining the productivity of agricultural land and proximal forests as well as of wildlife and fisheries all over. There has been hardly and substantial visible benefit of rural development and tribal welfare measures insofar as the land based productivity is concerned. Electricity, roads and other civic amenities wherever provided have not made any tangible contribution to the economic well of these people. Their dependence on the marginal farmlands and the ‘commons’ has remain unabated. Further, the accumulated diversion and degradation of forests outside the reserved forests system to agriculture has decimated the ‘commons’. The managements of reserved forests has all along had a strong leaning towards productions and harvesting of timber and bamboo, and has consequently failed to involve the people. A major development project viz the Bailadila Iron Ore Project, has not given any benefit to the local people but has only caused them deprivation of land and river pollutio

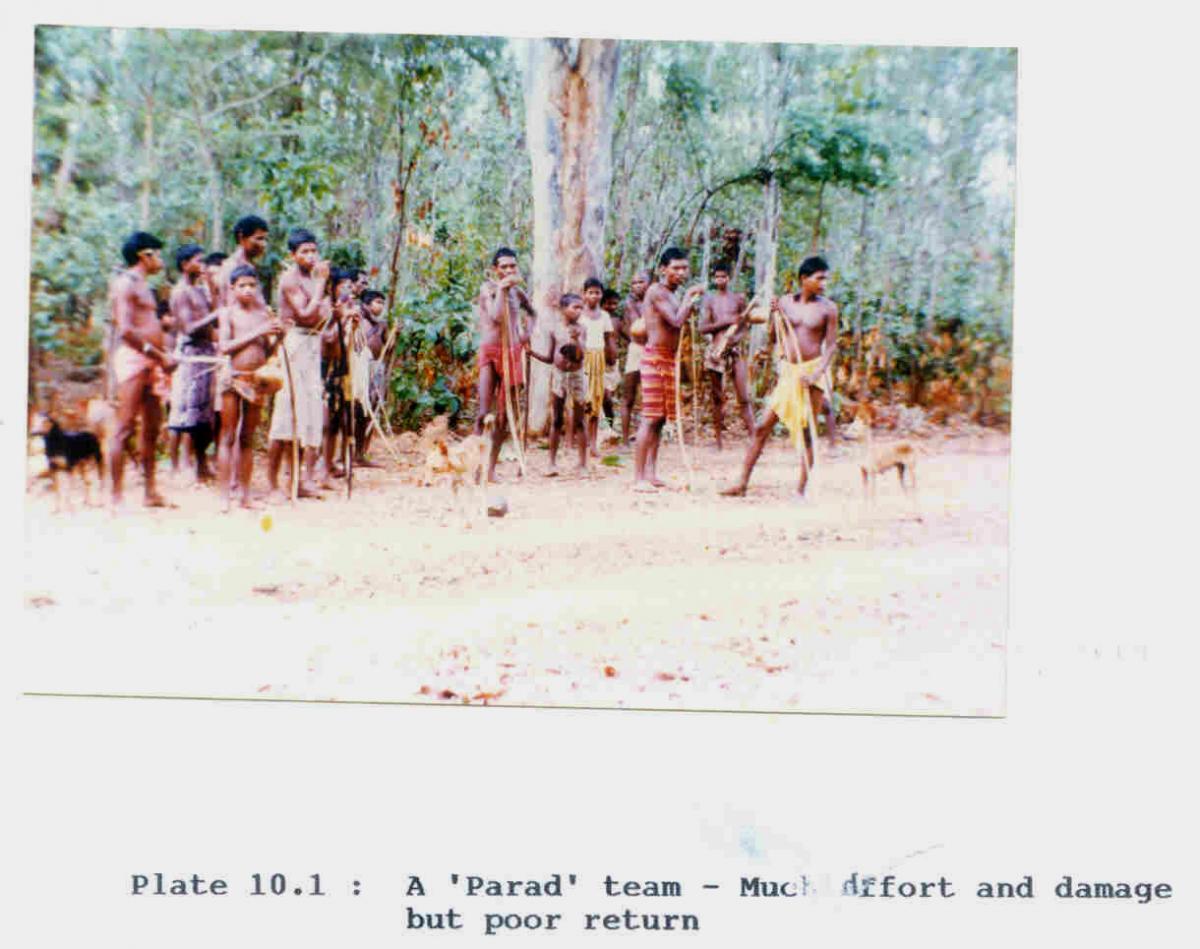

Likewise the Pine Plantation project, mercifully since abandoned. Aimed at production of industrial wood by converting prime natural and diverse sal forest. Even from purely economic conditions its merit was highly questionable vis-à-vis the economic returns from the standing natural forests. If seen from the local people’s and overall environmental angles, this would have been an unmixed disaster. The combined impacts of such ‘development’ without regards to concern of local people, less than perceptive as well as inadequate inputs into tribal welfare, non-involvement of people in the conservation of forests, and the deteriorating Landuse has led to impoverishment of the quality of life with no signs of reamelioration on the horizon. Notwithstanding the simplicity of the people, there is hence an undercurrent of alienation, which is what is perhaps nursing ‘imported naxalite’ insurgency and manifesting itself in the form of revival of ‘parad’ (ritualistic community hunting) with vengeance and its extension even to Inderavati National Park. The ecological processes have come under severe stress with pronounced soil erosion of farmlands and impoverishment of water regime. Sustenance linked pressures and vengeful ravage have than led to marked attrition of biodiversity and wildlife values. Unfortunately, the trend continues because either the issues are not understood or they are side tracked in the sway of expediency.

It is necessary to understand this present situation in order to set the perspective in which the impacts of the Bodhghat project have to be appraised. Today’s situation is such that both the natural and people related values are already depleted and under stress. This aspect is being emphasized because the present partial degradation of forests and substantial depletion of wildlife cannot be regarded as a bench mark situation for evaluation of impacts. The realistic bench mark situation for such evaluation would be the one where effective rural development has ameliorated the rural ecosystem and rationalized the dependence of people upon forests. In such a situation the restored status of flora and fauna would approximate with the optimal carrying capacity levels and be also available as a productive renewable resource for the people.

Bodhghat Hydroelectric Project is visualized by the planners as a means of national development with the ultimate aim of benefiting the people of the country. On the same analogy appropriate rural development of forest living people and conservation of forests and wildlife is no less an important aspect of national development because it holds key to environmental security through care of basic life support systems. Not only this, if the rural development and forest and wildlife conservation become more effective, the health of the catchment and hence the life and utility of such projects can be better secured

In seeking to access the impacts in this perspective and in relation to the ‘imagined’ bench mark situation, it is not intended to transfer the burden of overall mitigation of accumulated adversities to Bodhghat project. What is rather intended to be brought home is the now inescapable need to balance the hitherto presumptuously assigned high priority to such projects vis-à-vis the much greater realistic priority that should be assigned to redressal of Landuse incongruities in the forested regions. If in the continuing sway of expediency a reconsideration of priority allocation is deferred, projects like Bodhghat will end up diverting more agricultural and forest land and augment rehabilitation pressures on residual land thereby aggravating stress on environmental values – both human and natural – which are already stretched to a near break down stress. While making this critique, later herein we also consider how rehabilitation and mitigation programmes can be better planned and implemented in conmparison to what is at present being contemplated or done. Let us first visualize the impacts

Flora and Fauna values

The main concern of the report is flora and fauna, particularly wild buffalo, and these values are reviewed in what follows. About 20 per cent of the forest area likely to be submerged is degraded. Of the remaining 80%, sal-mixed (30%), miscellaneous with bamboo (40%) and reverine (5%) are extremely important from the point of view of wildlife but some of these areas particularly those close to the villages are also required by the people for their use. Away from the villages these forests have values as a productive timber, bamboo and MFP resource. Particularly notable id the occurrence of Xulia xylocarpa in these forests. Extensive presence of bamboo enhances habitat value for wildlife. Occurring in narrow but long strips along river banks and on river islands, the riparian habitat is vital for all wildlife, The river bed grasslands providing green forage during summer are crucial for wild buffalo. However, no evidence of wild buffalo was recorded in the study area. Except n the vicinity of the villages, the forests are in a very good condition both with respect to density and regeneration status.

As already stated the sal-mixed, mixed-bamboo and riverine forests-grasslands have a high potential for wildlife, The main species of which evidence was recorded are gaur, chital, barking deer, giant and flying squirrels, porcupine, leopard, jungle cat, hyena, sloth bear and otter among the mammals. Among the reptiles the Gangetic soft shell turtle, a species in Schedule-I of wildlife (Protection) Act was recorded as well as python and a few species of snakes and small lizards. Mugger also reportedly occurs along the Inderavati river. At least 12 species of fish were recorded. In all 127 species of birds were seen, the notable being openbill and white storks, black ibis, spitted sand piper, crested hawk eagle, marsh harrier, crested serpent eagle, jungle bush quail, red jungle fowl, painted spur fowl, pea fowl, emerald dove, Alexandrine parakeet, pied kingfisher, pied hornbill, six species of woodpeckers, golden and black headed orioles, racket tailed drongo, scarlet minivet, paradise flycatcher and a number of other species of flycatchers, warblers, bushchats, wagtails, munias and buntings. Although mot seen during the study, the hill myna is an important bird, locally endangered in Bastar because of extensive trapping for trade as a bird mimicking human voice. An important feature of the Bastar avifauna is the it comprises a mixture of species from Central Indian and Malabar regions

The frequency of all the above mentioned species of wildlife is rather low and this id attributable to habitat damage from fires and wide spread hunting, including ‘parad’. Of the 181species of flowering plants recorded, over 50 have food value for wildlife. Because of the survey time being summer, the list of recorded plants id low particularly with regard to grasses and herbs which are important sources of food for wildlife.

The much depleted status of wildlife as compared to potential carrying capacity and the presence of deleterious forest decimation practices like the forest fires are directly traceable to the impoverished economy and a growing feeling of alienation. Forest fires and the ‘parad’ have been an aspect of timeless tribals traditions but earlier the brunt was taken by the buffer of private and community forests sparing the remoter forests which are what comprise today’s reserved forests (Plate 10.1). This buffer now having been destroyed, the incidence of similar practices from a mush higher population is ravaging the remoter reserved forests and their wildlife potential too.

As far as the flora and fauna values of the forests affected by the project are concerned, it may be stated that intrinsically these forests are diverse and capable of supporting varied wildlife in abundance. The forests, the river islands and the bank area together are a potential habitat for wild buffalo. However, it must also be stated that in its present form the habitat is somewhat degraded and the status of major mammals poor. The wild buffalo itself is no longer present in the affected area. The status of smaller mammals is fair, whereas the diversity and status of bird life is still good. Aquatic fauna is depleted and so is the case with reptiles – terrestrial and aquatic.

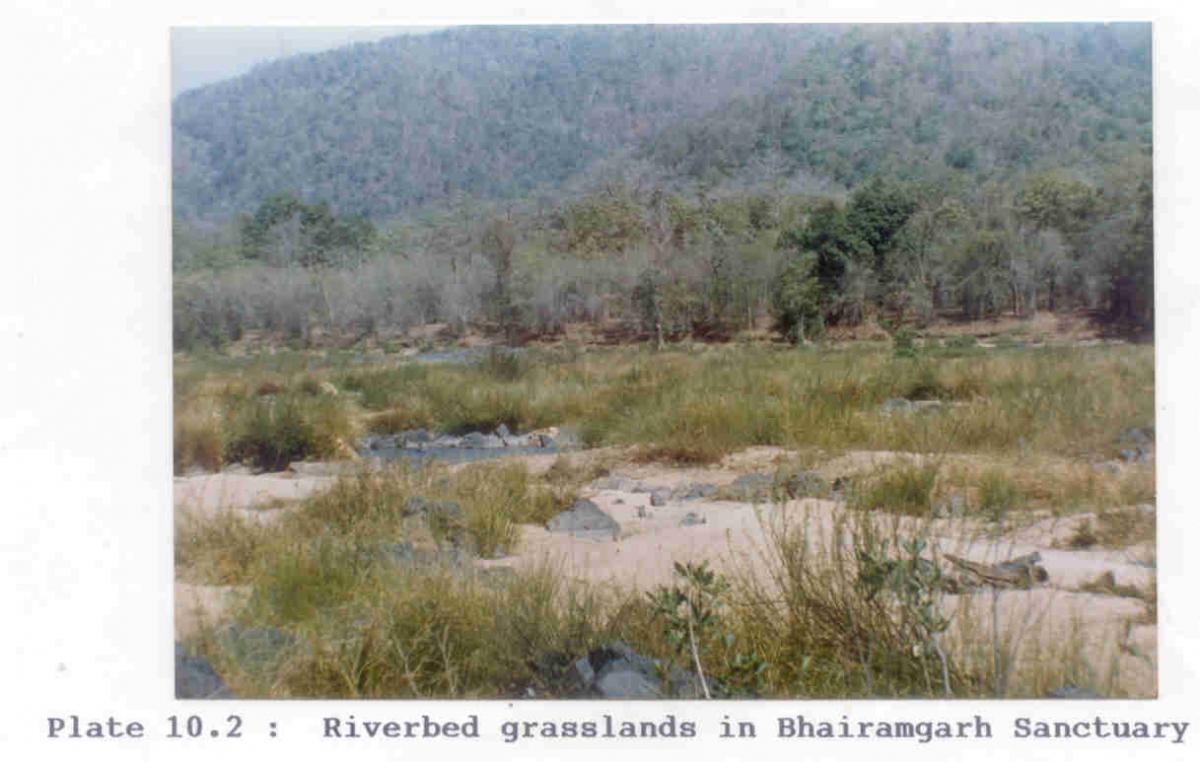

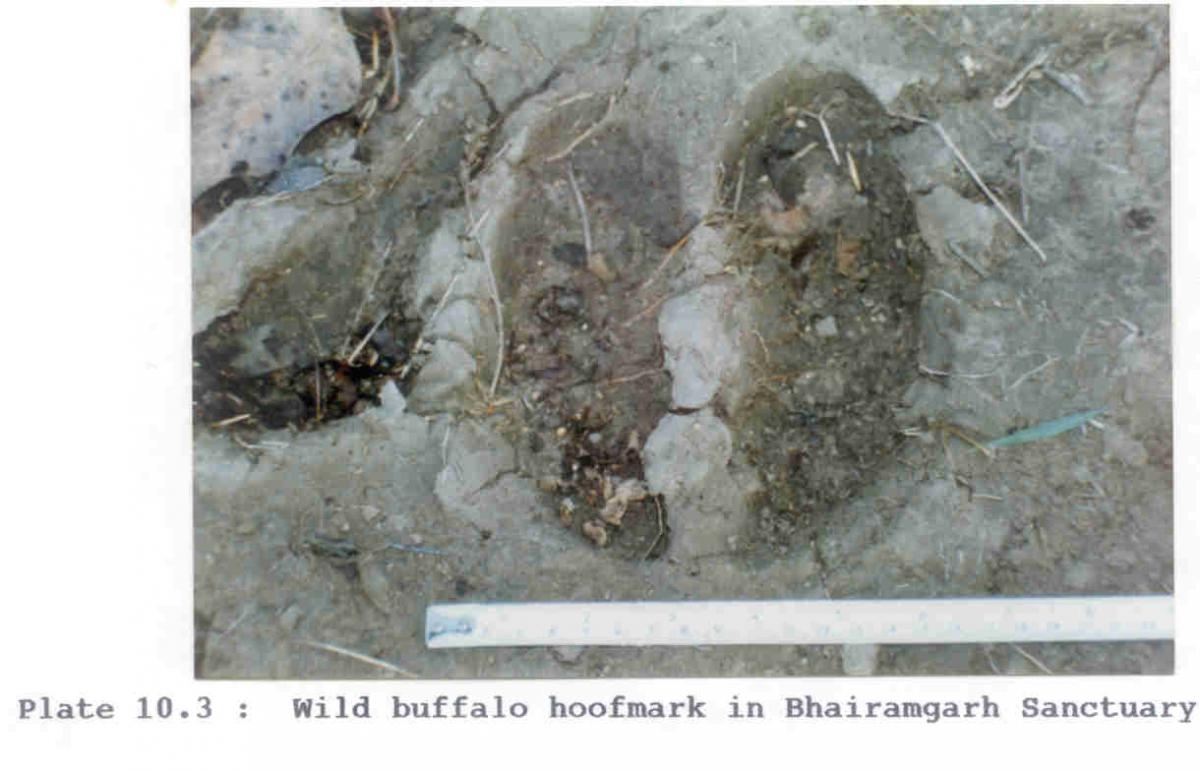

It was our special brief to look into the downstream impacts of the project upon wild buffalo conservation. Historically wild buffalo was present in the entire area on both banks of Inderavati downstream of the project. However, only two small populations now survive i.e. in Bhairmgarh Wild Buffalo Sanctuary and Inderavati National Park, both to the south and south – east of the river. A general survey was conducted of the downstream areas including Bhairamgarh and Inderavati. The former is just 60 km downstream of the Bodhghat project site. Inderavati accounts for Bhairamgarh’s entire southern boundary of about 15 km length. As already stated in the chapter on wildlife, we encountered fresh wild buffalo evidence in Bhairamgarh Wild Buffalo Sanctuary particularly in the parts close to the river as well as on the grasslands in the river bed itself (Plates 10.2 and 10.3). As far as Inderavati National Park is concerned it is much further downstream and no major impacts of Bhodhghat project are visualized in the area. However, the impacts on wild buffalo habitat in Bhairamgarh Sanctuary is bound to be severe and critical mainly brought about by the inevitable change in the regime of the water discharge. This is because the Bhodhghat Hydel Project will mainly cater to the peaking power requirements in the evening and early night hours, say from 6 PM to 11PM. All the four turbines will operate together this period and the rate of discharge is likely to be many times the normal lean summer discharge. This suddenly increased heavy discharge may take about three hours to reach Bhairamgarh Sanctuary where it will flood the river bed grasslands between 8 PM and 11 PM. This will coincide with the main foraging time of wild buffalo in summer, when such river bed grasslands are their critical food resources. The changed water discharge regime due to the project will thus severely jeopardize wild buffalo habitat in Bhairamgarh Sanctuary. This is particularly so because out of the total area of the sanctuary the prime wild buffalo habitat is only about a fourth of this area falling in compartment numbers 80 to 85 and 87 to 89. This prime wild buffalo habitat lying on the southern bank of the Inderavati river and both sides of ids tributary Dhangujusa nala is the proposed core area of Bhairamgarh Sanctuary.

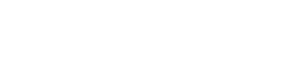

While considering downstream impacts it also needs to be mentioned that Bhodhghat is going to be very large reservoir. The enormous quantity of water held here will naturally be the justification for more downstream hydel projects. This is because a persistent drop in Inderavati downstream, right through its course upto confluence with Godavari, provides the scope for such projects. It is also common knowledge that five hydel projects (Kutru I, Kutru II, Nugur I, Nugur II and Bhopalpatnam) are planned on Inderavati before the major multi purposes project at Inchampalli in the Godavari downstream of the Inderavati confluence. It will not be justified to gloss over the very major impacts of five hydel projects because their viability as well justification would essentially derive from the large quantity of water held by Bhodhghat. We were given to understand that none of the downstream projects is being contemplated right away. However, the consideration for their subsequent execution is inevitable.

Am important criterion for environmental impact assessment of river valley projects is not to consider a single project in isolation. It is, therefore, necessary to visualize the impacts of the five projects on Inderavati, with reference to the inescapable and major landscape modifications and impacts on flora-fauna, particularly upon the conservation of wild buffalo. On the basis of preliminary details of these proposed projects as reported in “ India’s environment 1984-85” (CSE, New Delhi), it is seen that if Kutru II Dam comes up at the proposed near village Idwara, it will almost entirely submerge the prime wild buffalo river grassland habitat in compartment numbers 84 and 85. Further, all these five projects are so planned that the discharge level from the tailrace of the upstream will nearly be at the same as the FRL of the immediately succeeding downstream project (Fig. 10.1). This will mean that almost the entire length of Inderavati river from Kutru I project area right up to Bhopalpatnam dam will no longer remain natural. The series of reservoirs which will come up will completely isolate the areas to the north and west of Inderavati from those on its south and east. This will impose a very severe constraint on gene flow of all biota and on the movement patterns of wild animals in this tract. Moreover, almost the whole of the rich riparian wildlife habitat will come under submergence. Thus both from the point of view of prime habitat and movement corridor, the series of these dams will cause irreparable damage, the unique natural and cultural landscapes with the free flowing Inderavati as the life line will also get drastically altered. It is incumbent, therefore, to take this fact into consideration and to account for the protection of these values if clearance for Bodhghat project is given.

Ecological Processes

The major impact on this account will result from the submergence of upstream values and a drastic change in the diurnal river discharge downstream actuated by the regime of power generation. In the area of submergence, instead of the free flowing river a large reservoir will come up. As a result the riparian ecosystem will change into a lake ecosystem, Thus while there will be a complete transformation upstream, the impacts of downstream, even if not as dramatic can be as far reaching. Ecological processes in a free flowing river given only to seasonal fluctuations will have to give way to those capable of withstanding diurnally fluctuating flows. Further, there will be much less flooding during the rainy season. This will mean that deposit of fertile silt in the riparian segments of Inderavati and its tributary nalas will be much lower. This is bound to affect their productivity. On the other hand the dry season flows will go up considerably affecting bank communities. The river islands, the river bed grasslands and the aquatic flora and fauna will be drastically affected.

Such impacts in ecological processes can be colossal if the downstream projects are also taken into account because together these projects will completely alter the free flowing river.

Compensatory afforestation

Man made plantations can never discharge the ecological functions of a natural forest and hence compensatory afforestation can never fully compensate for the biological values to a development project. Although considerable effort has been made by MPEB authorities to organize compensatory afforestation with the help of the State Forest Department, the results appears good only insofar as the survival of plants is concerned. A major deficiency is the non-involvement of nearby people. Such involvement could be forthcoming only if rights of usufruct and even sharing of revenues were offered to the people.

People related impacts

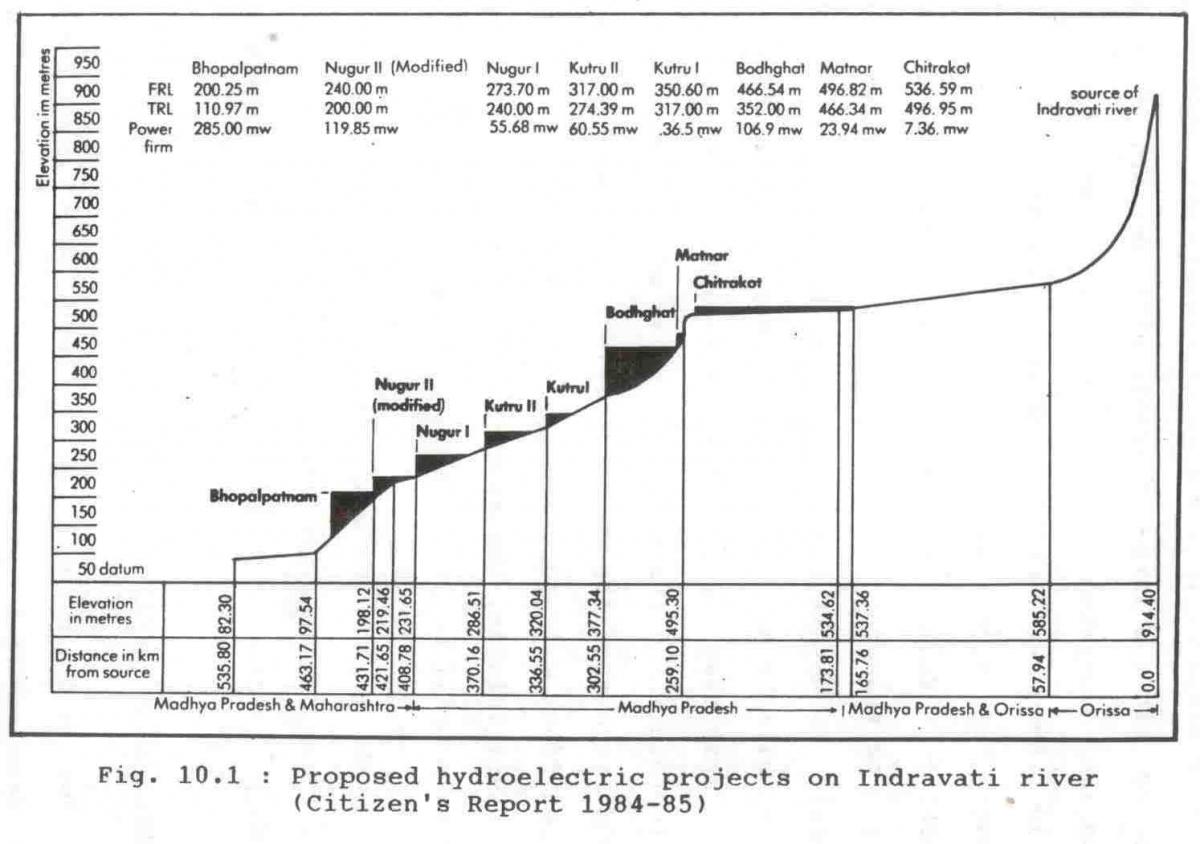

Earlier herein we have discussed at length the prevailing socio-economic condition of the people and its influence on the conservation of forests and wildlife. The picture as already stated is depressing because the equations between the land and the people are under great stress (Plate 10.4 and 10.5). Such being so, if the project causes a substantial area (137.83 sq km – 57 sq km forest and 80.8sq km non-forest) to be diverted from the current use of the people, the pressure equations in the residual area will come under an even greater stress. This is to be expected because the affected people will ultimately have to be rehabilitated in the same tract. Land for land compensation is neither visualized nor is it possible. As per the rehabilitation plan, the land in the affected area will be acquired against compensation and the affected people including those landless will be provided small parcel of land at the rehabilitation sites. All the rehabilitation sites essentially are the rural commons of the villages already existing there. They are meeting timber, bamboo, fuel, minor forest products and pasture needs of the existing villages. Thus even if better agriculture facilities are provided at the rehabilitation sites, there apparently is no provision for meeting the ‘commons’ based needs of the existing and inducted population. A small agricultural holding without intensive inputs e.g. assured irrigation, improved seeds and fertilizers cannot give economic independence to these people. This is bound to lead to further overexploitation and inevitable degeneration of their resource base in the ‘commons’, particularly the forests.

It is worthwhile to have a look at the independence of the people upon common property resources. Our study in the eight sample villages in the submergence area has shown that income from agriculture provides only 55% of the sustenance. For nearly the other half of their sustenance, the people depend upon the common property resources (Appendix 10.1). Seen in this light the rehabilitation programme, as being contemplated is not going top sustain the people in the long run. More specifically the much smaller agricultural holdings at the new sites, despite a somewhat higher per unit area yield, will lead to a lower per capita agricultural production. Likewise the per capita availability of goods and services from the ‘commons’ will also fall because in the rehabilitation sites a much larger number of people will be sharing a much reduced area (due to appropriation for rehabilitation) of common property resources.

In fact the rehabilitation plan suffers from the same deficiency which has all along affected rural development and tribal welfare in the forested regions all over the country, including in Bastar. The central issue here is the compatibility of the traditional utilization practices in the changed man to land ration. When the per capita availability of land has drastically fallen due to population rise and degradation from abuse and overuse, the only way to ensure economic well being is to aim for enhancing per unit area productivity, whether the land is privately owned or community shared. Also only when such sustain ably productive landuse meets the minimum needs of the people, there can be assurance of environmental security. Since much of the area of the Bastar district is hilly, undulating and having marginal soils, traditional or intensive agriculture cannot rationally be the dominating landuse. There is need to go into the causes of and remedy for the accumulated degradation of land from shifting cultivation, marginal land farming and damage to forests from needless burning and to wildlife from unsustainable hunting as well as habitat ravage. It is necessary to give up farming on area not permanently fit for agriculture and to restore the sites by a resort to tree cropping (silviculture, horticulture or sericulture) or to ranching (including deer farming or other wild animal / bird farming). Of course this also implies that concerted efforts should be made towards enhancing the productivity of agricultural lands which are amenable to sustained cultivation. What is also implied is the adoption of such land utilization practices which can yield best economic results without causing land degradation. Such an approach can be termed as Ecodevelopment or ecologically sustained economic development.

The strategy will be to consider the whole track around a rehabilitation site as an integrated development area. Thus the ‘commons’, the area for rehabilitation would inevitably be taken off, will form part of this development area. The measures as an integrated package will address private lands of existing and rehabilitated people as well as the forests and pastures comprising the ‘commons’. Animal husbandry, development of fisheries (including regulation of fishing in free rivers, ponds etc.) and other supplemental practices e.g. agriculture, forest and sericulture based cottage industry will be a part of such an integrated package. The key feature in such a plan will be the realistic involvement of people right from planning, through implementation, to allocation of benefits. Rehabilitation organized in this manner will not suffer from dearth of land and while meeting the onus of the project, will go to bolster environmental security while providing sustainable and substantial benefits to the people. It must be accepted that forest conservation is not going to be possible without the full cooperation and involvement of the local people. This in itself cannot be forthcoming unless people directly benefit from forest conservation. Such benefit can accrue to them in the form of a reasonable share of the returns from timber, bamboo and other minor forest products which will be harvested commercially on a sound, silviculturally sustainable basis. In not too long a run this will cease to imply to any loss of forest revenue because with better fire protection and tending inputs from the people, who will have a stake in the forests, the per unit area productivity will go up and offset the deficit due to allocation of people’s share. Their stake in conservation can be further enhanced initially be promoting game farming in fenced forest patches for the people’s use, while allowing the free ranging populations to recover. Their cooperation in such recovery should be sought by assuring that once the population status of game animals and birds goes up, the community will have exclusive privilege of regulated hunting. Such assurances, the implementation of which should be taken up in a package form right away, cannot fail to involve people. Care of the common property resources and intensive attention to sustain ably culturable holding in this manner can in a short time reverse the decimating trends and quickly thereafter built up productivity. More importantly this approach can assure economic well being of the tribal people without giving them cultural shock. In switching over to such a rural development model ideal for the forested regions, there will be an inescapable gestation period of 3 to 5 years. This will be because many agricultural holdings will switch over from annual cereal crops to sericultural, horticultural or silvicultural crops which may take a few years to yielding. The measures under the integrated development plan will however provide employment which can sustain the people through this ‘gestation’ phase.

Needless to say that adoption of such an approach to rehabilitation will go beyond the realm of the activities of the Bhodhghat project authority. The Revenue, Development and Forest authorities will have to involve themselves in working out and implement such a package with resources provided by MPEB.

Finally, at the risk of reiteration it has to be stated that unless the local people are taken care of in the above manner bringing them economic well being without undermining environmental security, there can be no moral justification to take up any major development project, Bodhghat or any other.

Last Updated: December 12, 2015