Introduction

|

The existence of a human population anywhere presupposes a complex of ethnic, social and biological influences and interactions. If these are not understood and adequately accommodated in resource management plans, the consequences can be serious and even disastrous (Lusigi, 198O). Human induced changes in wilderness habitats and steadily increasing extinction of species are only some grave consequences of inadequate resource management planning. Urbanization, industrial developments and infrastructural expansion for transport, telecommunication and energy are few of the human induced changes that normally pose threats to the natural environment. Although the impacts of the major developmental activities involving construction of large dams and barrages have been more significant on the natural environment (Anon, 1994), the fact that the linear expansion and upgradation of railway lines, roads, irrigation canals, power transmission lines and pipelines are more frequent development actions, emphasises the urgency of assessing the potential threats to wildlife consects (Plate 1.1).

Internal fragmentation of once pristine natural areas by road, rails, powerline, fences, canals, and other human induced changes in landuse have been fairly well established (Temple et. al, 1984). One of the most rapid and obvious effects of fragmentation is the obstruction of migratory movements of animal species leading to the gradual elimination of species. Several barriers affecting the contiguity of forest habitats have been recognised. One significant type of barrier in many landscapes is road (Oxley, et al., 1974; Mader, 1984). In Oregon, Dusky-footed Woodrats (Neutoma juscipes) and Red backed Volves (Elethrionomys occidentalis) never used the highway Right-of-Way (RoW) (Adams and Gis 1983). A nine year study in the Kansas grasslands confirmed that a few Prairie Volves (Mierotus oetrogaster) and Cotton Rat (Sigmoden hispidus) ever crossed a narrow road of 3 m width that bisected a trapping grid (Swihart and Slade, 1984). What constitutes a movement barrier is highly species specific. The road can act as barrier even for animals as large as Black Bears (Ursus americanus) (Brody and Pelton 1989). Elephant populations in our country have been affected by the above mentioned linear developments in different states. Construction of road in the forested hills dissected the once continuous elephant range in Arunachal Pradesh (Johnsingh, 1986). Railway lines, recognised as yet another form of landscape barrier, have been known to obstruct animal movements. Obstruction of elephant movements between south of Shencottah pass and Idukki Periyar hills could be attributed to the presence of railway line (Johnsingh et. al., 1991). A 14 km long Rishikesh-Chilla power channel, Haridwar-Rishikesh railway line and road track and Kotdwar-Lansdown road restricted the movement of elephants, mainly the female groups between Rajaji and Corbett National Parks (Johnsingh et. al., 1990). Sometimes developments of linear nature pose, direct threats to survival of wildlife species. A study of the effects of the vehicular pressure on the roads in Everglades National Park revealed that 73% of snakes were either injured or killed because of accidental run over by the enhanced vehicular movements on the newly constructed road (Bernardino and Dalrymple, 1992). Chellam and Johnsingh, 1994 have discussed that highways and railway line across the Gir National Park and Wildlife Sanctuary caused increased incidence of fire hazard and lions being run over in the track. Field studies suggest that roads obstruct the movements and thus bisect the gene pool by dividing animal populations into two fractions on either side (Mader, 1984). Impacts of transmission line on wildlife have also been now recognised. More than 300 Cape Vultures (Gyps copotheres) were electrocuted due to 88 KV suspension powerline towers in Western transroad in South Africa (Ledger and Annegarn, 1981). Powerline tower construction by Bihar State Electricity Board across Ganges in Barauni have reduced the number of migratory waterfowl visiting this area from 300 to 50 (Gammon India Limited, Pers. Comm., WII, 1994). The rising global demand for energy has been met to an increasing extent by the use of fossils fuels, especially oil, which was cheap and plentiful. According to World Bank Report (1979) world's energy consumption has increased 600 percent between 1900 and 1965 and an increase of another 450 percent till the year 2000 is projected. The present coal production from open cast mines of about 64 million tonnes (1983-84) has been increased to 137.00 tonnes in 1989-90, and is sought to be increased to 192 million tonnes in 1994-95 and by 2000 A.D. to 225 million tonnes (Sinha and Pradhan, 1985). Energy production and transformation processes are claimed to be the origin of atleast 50 percent of the environmental problems (Ephrussi, 1990). All the energy vectors, from source to end use, have environmental impacts. These impacts can be local, regional and global. The impacts have been recognised at all sources including those from tapping of energy, transportation of fuels, transformation and end uses and also further beyond in the disposal of the end wastes. Mining an early step in energy tapping source is a devastating operation, especially, if it is an open cast mining. Its associated problems are deforestation, waste disposal, water, air, land and noise pollution, and physical destruction of vegetation and associated faunal species (Gadgil,1973; Crawford, 1978; Ray, 1985). Transportation of coal is generally executed by rail and road. The transport of coal in all its forms involve emission of fugitive dust. The estimate for atmospheric emissions of SO2 (780 kg/trip), NO2 (4855 kg/trip) and particulate during loading and unloading may be 2285 kg/trip, when a unit train carrying 1143 ton coal makes a round trip of 985 km (Szabo, 1978). Marine transportation is the most important means of transporting oil from production to consumption areas. The statistics of oil spills per year in the marine environment showed that ca. 12,000 barrels of oil spills every year. A 75% of human caused spills comes from ships. Offshore oil production accounts for ca. 2000 barrels of spilled oil/year, and the cost of cleaning up operation is US $ 1000/barrel (USEPA, 1978). Gundlach (1977) discussed that the biological impacts of Metula (ship) oil spill in Atlantic Ocean showed that 40,000 tonnes of crude oil deposited along the shoreline, resulted in the death of about 3000 to 4000 birds, destruction of mussel beds, marsh and fish life. The total record of accidental oil spill in Indian Ocean (north of the equator till 1982 resulted from 15 tanker disasters and 3 blow outs (Couper, 1983). Deposition of tar-like residues on the beaches along the west coast of India is approximately 750-1000 tonnes per year (Dhargalkar et al., 1977). 1.1 PIPELINE PROJECTS AND ENVIRONMENTAL CONSIDERATIONS These pipelines are efficient and economic system of transporting oil, gas and petrochemicals and other petroleum products from their source to the refining units and to distribution points. Considering the rate of expansion and upgradation of pipelines in India (Table 1.1), it is inevitable that some sections of these pipelines totalling to 4916 km would traverse through important wildlife habitats harbouring, terrestrial and aquatic wildlife species of great conservation significance. A 25 km section of proposed Hazira-Bijaipur-Jagdishpur Pipeline (HBJPL) Project would traverse through the proposed Great Indian Bustard Sanctuary (WII, 1993). Chambal Wildlife Sanctuary that holds the world's largest population of Gharial (Gavialis gangeticus), and Ramsagar lake, an important wetland that acts as satellitic buffer for migratory birds on their way to Ghana Keoladeo National Park are en route the proposed pipelines. Table 1.1 Length (km) of pipelines proposed/underway in India and the neighbouring countries

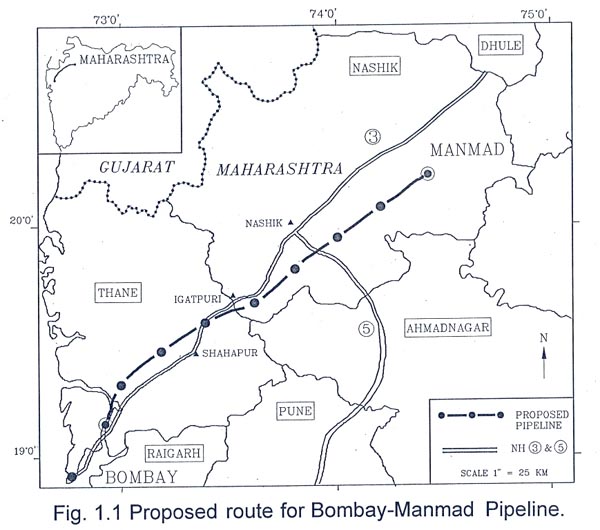

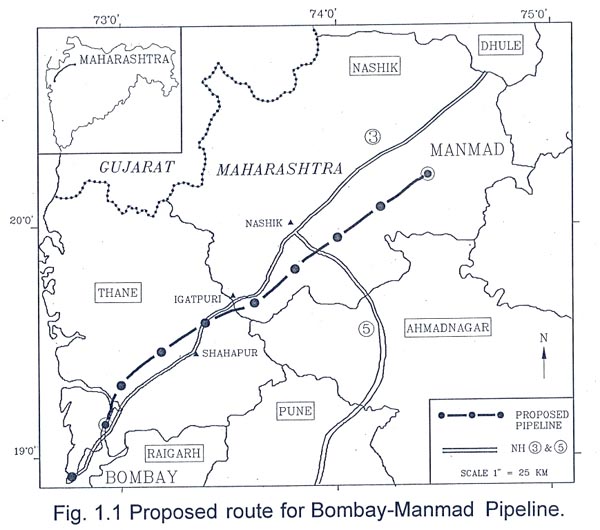

Source: Ives, 1993 Out of six rivers en route the Haldia-Barauni Pipeline (HBPL) Project, the river Ganges and Rupnarayan are important Gangetic Dolphin (Platanista gangetica) habitats that are crucial for long term conservation of the existing range of the Gangetic Dolphin population. The sighting of Baer's Pochard (Aythya baeri) in the Harohar river is a finding of significant ecological interest (WII, 1994). This threatened species of bird (IUCN Red Data Book, 1994) is likely to be impacted by the HBPL Pipeline Project. Even with economic and social, benefits of pipeline installation, impacts of pipeline expansion projects on land- scape, soil, water regime, vegetation and wild fauna can not be ruled out. Severe disturbances caused by laying of pipelines have been studied by Putwain and Gillham (1982). The original heathland vegetation did not recover on the pipeline route. These irreversible changes in the vegetation have been associated with considerable changes in the soil properties that have been caused by project related actions. Often, coarse grasses, sedges and rushes have become the dominant plants on pipeline routes, that completely replace the original heathland vegetation (Moffat, 1975). Low regeneration, enhanced weed dominance, and biotic pressures have been observed in the RoW of the existing section of HBJ pipeline route (WII, 1993). The lack of scientific and systematic EIA studies have been one of the contributory factors in delaying the decisions on the implementation of major developmental projects in the past. Distortions in cost-benefits ratios of major river valley and refinery projects (Singh et. al., 1978) have largely resulted from delay in decision making in absence of systematic impact assessment studies. Pipeline projects would suffer from similar distortions in their cost benefit analysis if systematic studies based on scientific reasoning are not initiated timely. The EIA study of proposed Bombay-Manmad Project is an effort to provide timely suggestion on environmental considerations and the incorporation of environmental safeguards both, at design and at implementation stages. 1.2 PROPOSED PROJECT: BOMBAY - MANMAD PIPELINE PROJECT

A 250 km long pipeline with a diameter of 45.72 cm, would be laid at the depth of 1 to 1.5 m below the ground in conformity with the latest International Specifications (OISD/API) will result in the shifting of the nodal point for loading of petroleum products from Bombay to Paniwadi, near Manmad which is well connected by the existing railway network. 1.2.1 Project design and its salient features Phase I: Phase II: Both the terminals will have pig launching and receiving facilities with monitoring and control facilities. To supervise and control the operations more efficiently the help of Supervisory Control and Data Acquisition (SCADA), Cathodic Protection System (CPS), Acoustic Leak Detection and Information System (ALDIS) and Fibre Optic Voice and Data Communication System (FOVDCS) techniques will be used. The proposed pipeline route would have the following major crossings.

1.2.2 Objectives of the EIA study In line with the requirements of MoE&F, the environmental impact assessment report which inter alia included the study of forest and wildlife especially, rare and endangered species and the flora and fauna along the pipeline corridor was prepared earlier. It was desired by MoE&F, Government of India that the impact of laying of pipeline through the forest be studied in consultation with Wildlife Institute of India (WII), Dehradun. Accordingly a consultancy was offered to WII by the BPCL, Bombay to undertake impact assessment studies with special reference to impacts on wildlife values. 1.2.3 The scope of work under consultancy offer to WII The following is the scope of work visualised under the consultancy offer to WII for impact assessment studies for the above project insofar as they relate to wildlife values. 1. assessment of the status of wildlife species and their habitats (terrestrial and aquatic) en route/along the proposed pipeline route. 2. identification and evaluation of the likely impacts on wildlife (endangered/ threatened) species and ecologically sensitive areas/habitats (forests/ scrublands/grasslands/wetlands) due to the proposed pipeline expansion. 3. outlining the mitigatory measures for the likely impacts that may be caused by the proposed project. 4. outlining the legal and statutory obligations to be fulfilled by the project proponent under the Wildlife (Protection) Act, 1972; Forest (Conservation) Act, 1980; and Environmental Protection Act, 1986. |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Last Updated: October 6, 2015