Discussion and Recommendations

|

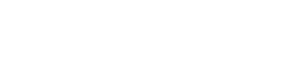

Wolf populations throughout India are on the decline. Their continued survival on the subcontinent is threatened by i) habitat loss, ii) loss of natural prey iii) direct persecution by humans and iv) diseases. Areas with any promise of long term survival for wolves are those that still have low human densities, low intensity agriculture, wild prey in the form of blackbuck, Indian gazelle, hare and rodents, and remote habitat patches that serve as good denning and rendezvous sites (Jhala and Giles, 1991). Our surveys in India limit such areas to parts of Rajasthan, Saurashtra and Kutch in Gujarat, central Maharashtra, and some portion of Andhra Pradesh and Karnataka (Jhala, 1993). Amongst all the above listed areas, parts of Kutch (including the areas proposed to be mined) seem to be having the highest wolf densities (probably in the world !). Areas such as these would serve as source populations from which wolves would disperse to adjoining areas (sinks) with less conducive conditions of survival and breeding. Due to the social organization within wolf packs, only a single adult male and female breed at any given time. A pack is likely to range over several hundred square kilometres and defend its territory from other wolves. This mechanism prevents wolf density from increasing beyond a threshold, which is ultimately dictated by food resources (Packard and Mech, 1980). For successful recruitment it is imperative that remote habitat patches are available for denning and rendezvous areas (where pups are kept till they are old enough to join the pack). Breeding may occur in less favourable habitats, but recruitment is negligible since human caused mortality of pups is very high in such areas. We found evidence of breeding wolf populations both at Mata-no-Madh and Umarsar. Thus breeding habitat is available at both these sites. However, direct human persecution during the denning stage was high, resulting in pup mortality. This threat could be addressed by a combination of a proper compensation scheme for wolf killed livestock, enhancing wild prey populations, conservation education, and law enforcement. As long as the local people do not resort to using poison for wiping out the entire adult wolf population in the area, an occasional loss of a litter would not pose a severe threat to wolf populations in the region. However, there is an alarming trend in Kutch of increasing use of poison for killing wolves. The lignite mining site at Panandhro provided a vivid example of the magnitude of habitat destruction that the proposed mines would cause (Plate 6). In case, all the three proposed mines and Panandhro area are mined, then surely the habitat would be so degraded so as to result in loss of all potential habitat for denning and rendezvous sites resulting in local extinction of wolf populations. A substantial amount of habitat destruction has already taken place both at Mata-no-Madh and Akrimota due to removal of several meters of soil in areas at both these sites to expose the Lignite zone. In spite of this scare the Mata-No-Madh area had high ecological value. We found evidence of 3 critically endangered species using this area; the wolf, caracal and the Great Indian Bustard. We propose that this site be set aside for conserving the endangered fauna of the region and the ecosystem processes that support their viable populations and mining not be permitted in this area. Akrimota is close to the Panandhro site, which is already an ecologically lost case due to lignite mining, heavy road traffic and thermal power plant. Even though the Narayan Sarovar sanctuary boarders the fringes of the Akrimota site, mining could be permitted in this area since it is likely to cause the least amount of ecological damage in comparison to the 2 other sites. If carefully regulated, the impact of the Akrimota mine and proposed power plant on the Narayan Sarovar Sanctuary could be minimised. The Sanctuary boundary commences along a steep ridge top while the mining is proposed on the Northern side of this ridge - a natural barrier that could help to minimise impacts. Regarding the site at Umarsar we recommend that mining be permitted along the southern fringe of the current road from Dyapar to Umarsar. The Northern area that contains climax Acacia nilotica forests be spared for its ecological, agro-pastoral, and wildlife values. It is also in this region that the habitat is continuous till Lakhpat and suitable for resident breeding population of wolves and other endangered wildlife. Our surveys in this region of Kutch have shown that the drainage system of Khari, Baktad, Kandonwali, Madhwali and Sugandhi rivers have a great potential as a conservation area (Figure 1b). We have found good populations of wolves, chinkara, Great Indian Bustard, and 3 sightings of caracal. The area is primarily grazing grounds of villages, revenue land and some reserve forests, with very little area under active cultivation. After surveying the existing Narayan Sarovar Sanctuary we believe that the above mentioned drainage systems have equally good if not greater wildlife values. We recommend that this area be given some form of legal protection. A sanctuary status seems to be the best option, since the prime economy of the area is agro-pastoralism. The large livestock population in the form of cattle is highly nomadic due to the highly seasonal productivity and drought prone nature of the area. This status would permit the current form of land use to persist with appropriate regulation but would prevent ecological devastation by industrial and other market forces.

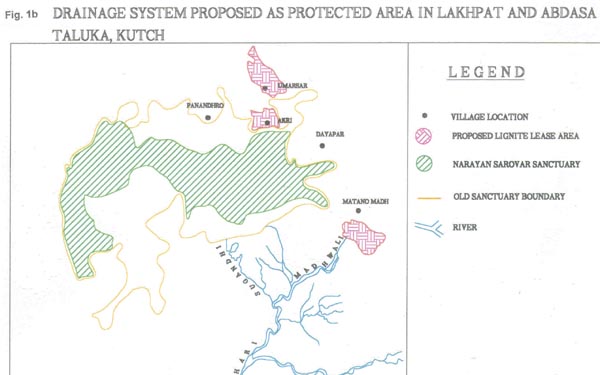

Reclamation of mine land is an essential regulatory condition for obtaining environmental clearance. In practice, majority of mine areas are reclaimed as grasslands or plantations. The Panandhro area has some portions where the mined areas have been back filled and plantations attempted (Plate 9).

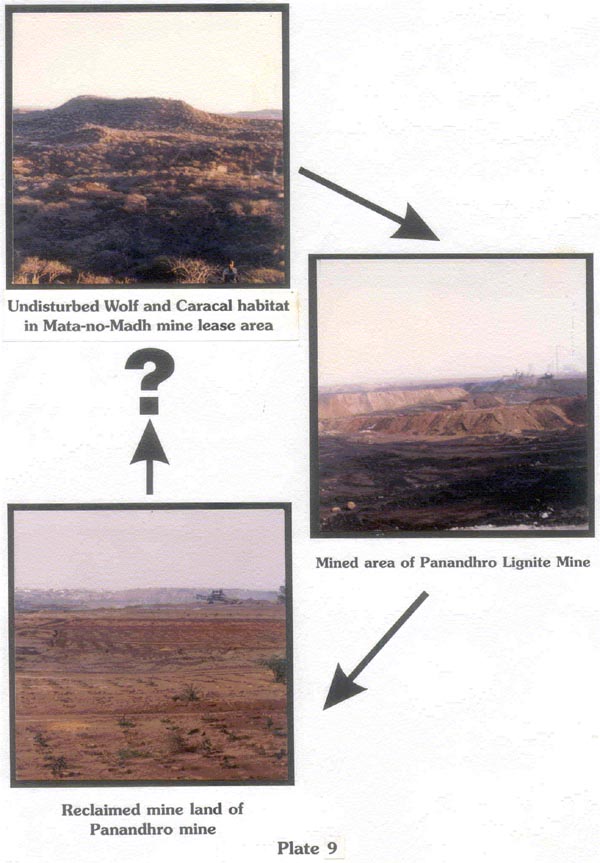

Similar kind of reclamation scheme is being suggested for proposed lignite mining projects. These type of reclamation plans fail to take into account the regional biodiversity and wildlife habitats. It is possible however, that by providing heterogeneity during reclamation that the values and functions existing on the site prior to mining may also be reestablished during reclamation. The integration of a diversity of habitats into the reclamation will not only provide food, nesting/breeding cover for a variety of species. The reclamation plan needs to be well designed after taking into account the edaphic, ecological and hydrological considerations within the area. Development of reclamation plans should be a consultative process involving ecologists, wildlife biologists/naturalists and the representatives of regional forest divisions. The GMDC scheme of reclamation and restoration for Panandhro Lignite Mine project leaves a lot to be desired at the proposed mining sites. It seems unlikely that the filler soil would support any diverse vegetation due to the total absence of top soil and any organic manure. In reclamation plans, of all the mine sites, economic benefits to people should remain a central theme. The over burden dumps should be stabilised and developed into parcels of productive forests to cater to the needs of the local people and the labour force. This would take off the existing pressure of resource extraction pressure from the buffer zone forests. This would be a one of the viable options for significantly reducing the unsustainable dependence of people on local fuelwood resource (Plate 10).

These added incentives of provision of resources to local people from the mine land will not only involve them in resource conservation but would also restrain their involvement in activities like poaching and killing of local wildlife species. Instead they would channelise their efforts into promoting local handicraft industry and other income generating alternatives. Construction of wetlands could be a possibility in post mining planning process. The mining plans of these projects envisage the creation of water bodies. If the water from them could be diverted to create wetlands, and associated upland habitats the regional biodiversity could be promoted and conserved. During the recontouring of the mine site all water ways, and diversions can be constructed in a manner that will allow shallow impoundments and channelisation of surface water into developing wetlands around which shorelines can then be installed once the mining operation stands completed. The wetlands should be gradually prepared for sustaining species of waterfowl & fish. There are several success stories of wetland development on mine lands (Doty and Lee, 1974; Brenner, 1987 & 1990). The project authorities should take lead role in creating similar productive ecosystem atleast in Akrimota site. We recommend that a professional agency be involved in developing and implementing the restoration scheme of the current and proposed lignite mining areas. This agency should be involved in planning the mining and extraction process and eventual restoration process. An appropriate budget be developed and allocated for this explicit purpose. We also suggest that initially hardy plant species that are drought resistant be planted in the reclaimed areas (eg. Prosopis juliflora). These should be replaced after about 10-15 years by native indigenous floral communities. Thus restoration is not a one time process but needs to be monitored and inputs provided for a period of 25-30 years following land fill. The GMDC could possibly involve the Gujarat Forest Department and a local NGO for assistance in their reclamation scheme. The GMDC does not speculate more roads even if all the additional 3 mines become operational. This would increase the road traffic phenomenally. We propose that an alternative form of transport for lignite be considered; in the form of a railway line or by sea. This form of transport would be more ecologically conducive. Mining activities result in local concentration of people; labourers, technical professionals, and traders. The GMDC has planned townships for their staff in the region. All these people whether willingly or unwillingly cause habitat degradation and loss of wildlife values of the land. In the adjoining industrial areas "foreign" labour been examples of forces involved in poaching. Increase in such intensive poaching activities could potentially cause great damage to species populations. Besides foreign labour brings change to local conservation values, an example is the use of poison which was not known in Kutch 10 years ago. All human populations need fuel; this is primarily obtained from fuel wood (at least initially). Such usage in semi-arid region, where woody vegetation takes several years to grow, would be devastating to the ecosystem. Care should be taken by GMDC to provide alternative energy sources to their direct and indirect employees. Also GMDC could develop schemes of promoting solar cookers and fuel efficient chullahas for use in the local villages of the region. This would ensure that the vegetation of the region is not severely degraded. As mentioned earlier, changes influencing any part of the ecosystem functioning are likely to effect top carnivore populations. Socio-economics of the local people are also critical in evaluating survival of wolf populations. Most industrial development schemes rarely benefit local populations. Technical staff, professional staff, as well as labour, in many cases, is imported. While simultaneously a sizable chunk of land on which local people depended for grazing, fuel wood, and other agro-economies is no longer available to them. This increases pressure on the remaining land area which in this case already has high pressure from livestock and village fuel needs. It is important that to prevent this cascade effect of ecological degradation that is set off by most development schemes a proper socio-economic strategy for the local people be planned and executed prior to the commencement of such large scale change in the land use pattern. We lack the expertise to plan such a scheme but stress the need and suggest that it should include ; 1) ways to improve the economic status of the residing local population within the acceptable social context, 2) reduce their dependency on the slow-recovering resources of the ecosystem, 3) the initiative should be such that they do not encourage people to migrate to this area. It has always been difficult to justify conservation especially at the apparent cost of readily conceivable economic development. The lignite mining lease areas have a similar dilemma, where there is a lot to gain economically within a "short" timespan while on the other hand the agro-pastoral economic value of the land, albeit for posterity, is hardly perceivable. Wildlife conservation values are subtle, rarely economical, but real. The increasing public opinion in favour of conservation suggests an increase in the awareness of these values amongst the people of India. The mineral wealth of India, if not exploited today, will remain in the safety vault.. of the earth for future generations. While the loss of species like the wolf and caracal would be permanent like that of the dinosaurs. The difference being that in this case it would be our economic agreed that would cause these extinctions. Technological advancement in the future is likely to result in the exploitation of this mineral wealth more economically and at a lower ecological cost. However, once extinction occurs, technology can not bring back the wolf and the caracal. The above argument does not suggest that all economic exploitation of the earth must cease. We merely suggest a strategy to do this wisely, with minimal impact on the highly sensitive processes and components of the arid Kutch ecosystem. The recommendations in this report, if implemented earnestly are likely to achieve an optimal compromise between the economic drive to mine all the lignite at the 3 proposed sites and preservation drive which strives to prevent any disruption of any ecosystem process. This EIA report outlines the likely impacts of lignite mining on wolves and their habitat and recommends ways to minimise the negative impacts. With the implementation of the recommendations in this report the GMDC is investing in a strategy that would bereft it from blame from future generations to be the agency responsible for local extinction of 2 endangered species and disruption of ecosystem process. |

Last Updated: October 1, 2015